László Gránásy1,2, László Rátkai1, Gyula Tóth3, Pupa Gilbert, Igor Zlotnikov4, Tamás Pusztai1

1Institute for Solid State Physics and Optics, Wigner Research Centre for Physics, P.O. Box 49, Budapest H-1525, Hungary

2BCAST, Brunel University, Uxbridge, Middlesex, UB8 3PH, United Kingdom

3Department of Mathematical Sciences, Loughborough University, Loughborough, Leicestershire, LE11 3TU, U.K.

4B CUBE - Center for Molecular Bioengineering, Technische Universität Dresden, Germany

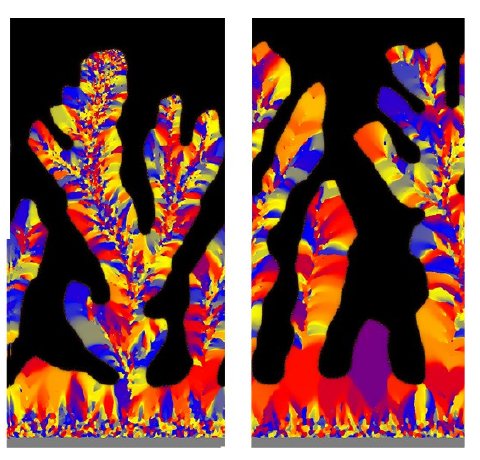

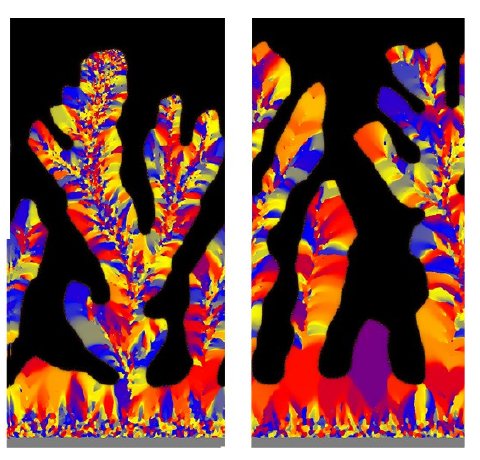

While biological crystallization processes have been studied on the microscale extensively, there is a general lack of models addressing the mesoscale aspects of such phenomena. In this work, we investigate whether the phase-field theory developed in materials’ science for describing complex polycrystalline structures on the mesoscale can be meaningfully adapted to model crystallization in biological systems. We demonstrate the abilities of the phase-field technique by modeling a range of microstructures observed in mollusk shells and coral skeletons, including granular, prismatic, sheet/columnar nacre, and sprinkled spherulitic structures. We also compare two possible micromechanisms of calcification: the classical route, via ion-by-ion addition from a fluid state, and a nonclassical route, crystallization of an amorphous precursor deposited at the solidification front. We show that with an appropriate choice of the model parameters, microstructures similar to those found in biomineralized systems can be obtained along both routes, though the time-scale of the nonclassical route appears to be more realistic. The resemblance of the simulated and natural biominerals suggests that, underneath the immense biological complexity observed in living organisms, the underlying design principles for biological structures may be understood with simple math and simulated by phase-field theory.